WASHINGTON — In 2011, after faltering debt limit negotiations with House Republicans brought America to the brink of economic calamity, President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden sat next to each other. to the fireplace in the Oval Office, with his top advisers on the couch. Although relieved to have narrowly averted disaster, they were stunned by what had happened.

Obama and Biden made a vow: never again.

They agreed that going forward, «nobody can use the threat of default or not raising the debt limit as a bargaining tool,» said a former Obama official involved in the tax discussions, who recounted the Oval Office meeting and the “lesson of 2011”. they all argued. “It made you hold your stomach. You couldn’t believe you were in this situation,» the official said.

The United States had just suffered its first credit rating downgrade. The markets were shaken. Consumer and business confidence was shaken. Stocks were affected. And recovery from the Great Recession was in question. Democrats avoided the precipice, agreeing to $2 trillion in spending cuts the GOP had demanded after negotiations on a “big deal” failed, but Obama and Biden agreed that the mere threat of default had taken a toll. price.

“They said: this is the sad lesson we have learned,” the Obama official said, describing the mood in the room. “It was an unimaginable self-inflicted wound in 2011.”

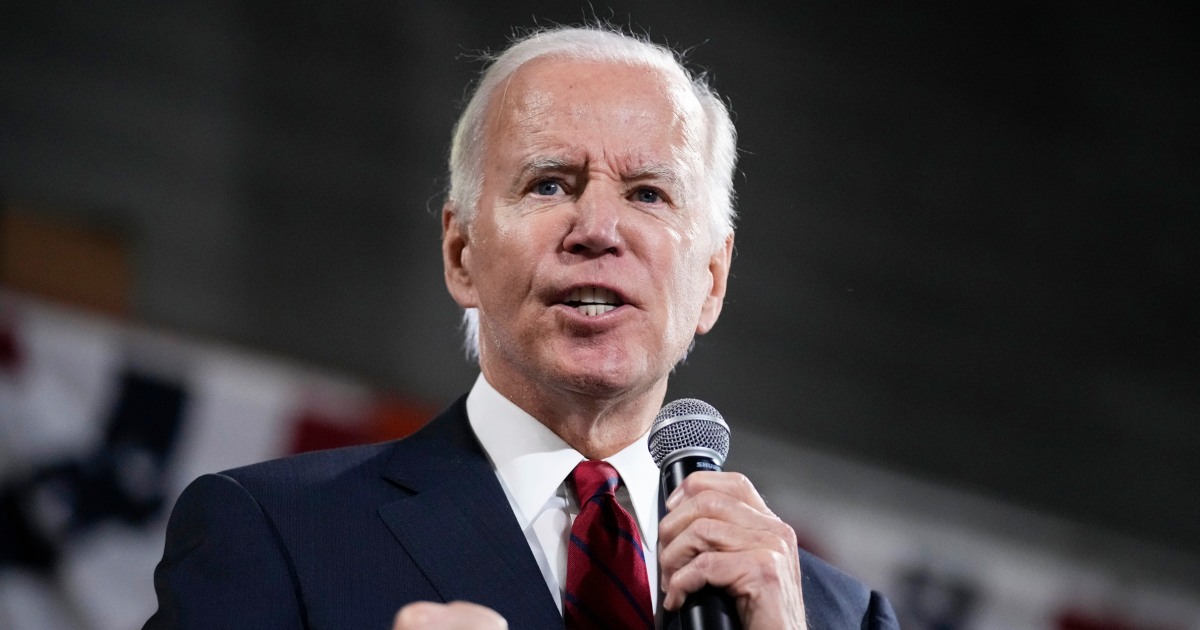

Twelve years later, Biden is executing on that lesson as he takes on a new Republican-controlled House that is similarly demanding spending cuts as a concession to extending the debt ceiling. He says that there will be no negotiations and that Congress must allow the government to pay its bills. “I will not let anyone use the full faith and credit of the United States as a bargaining chip,” Biden said Thursday in Virginia.

His stance has drawn a rebuke from House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, who said he is «disappointed» but has stood by his call for spending cuts. As in 2011, the GOP chairman has a House majority filled with ideologically driven conservatives who want to use the debt limit as leverage to force budget changes on a Democratic-led Senate and White House.

“Here’s the leader of the free world banging the table, being irresponsible, saying ‘no, no, no, just raise the limit, make us spend more.’ No. That’s not how adults act,» McCarthy told reporters on Capitol Hill last week. “Let’s find common ground and eliminate wasteful spending to protect hard-working taxpayers.

“So the longer you wait, the more you put US fiscal risk at stake.”

The showdown raises the stakes for Biden and the Republicans ahead of what Treasury says is a June 5 deadline to act or risk default. Democratic leaders in the House and Senate back Biden and demand that McCarthy introduce his plan and pass it in the House before any further discussion. It sets the debate on a different trajectory than in 2011, when Obama tried to broker a budget deal with Republicans in exchange for raising the debt limit, which faltered several times and led the US into days of default. It’s unclear how this one ends.

David Schnittger, who worked as deputy chief of staff to then-President John Boehner, recalled that in 2011, House Republicans could force the White House to the table by securing enough votes behind their initial offer: adding a ceiling increase of debt to a balanced budget amendment.

“We may eventually see House Republicans come up with a plan to deal with both the debt limit and the spending problem. That’s what the House Republican majority did in 2011 with the ‘cut, cap and balance’ bill,” Schnittger said in an email. He argued that the law that requires Congress to raise the debt ceiling, rather than automatically raising it, exists to «force a discussion or negotiation» on budget policy when debts mount.

It’s unclear if McCarthy can find 218 Republican votes for a bill of his own in his narrow majority in the House. And so far, Republicans don’t have a unified plan for what spending they want to cut.

After 2011, the Obama White House took a hard line when the debt limit deadline was reintroduced in early 2013. Then-White House spokesman Jay Carney said in January of that year: “The Congress can pay its bills or it can not act and put the nation in default.

House Republicans relented, attaching a debt limit extension to a token measure calling for passage of a budget.

Under that stance, Congress, under a GOP-led House, extended the debt limit three more times, in October 2013, February 2014, and November 2015, either with a token supplement or a bipartisan budget that both parties had agreed. The threat of default was off the table. During that period, spending picked up again, with Democrats seeking more domestic money and Republicans backing more military funding.

When asked about Biden’s position and criticism from the GOP, the White House said the president «is behind no one» in pursuing bipartisanship, but said the no-deal stance from 2013 on the debt limit succeeded.

«Asking why it’s been 12 years since the Democrats stopped paying bailouts in exchange for the Republicans not triggering an economic crisis is a self-defeating question,» White House spokesman Andrew Bates told NBC News. “In 2011, the Obama-Biden administration negotiated in good faith, but the recklessness of Republicans in Congress dealt a historic blow to our economy. That is why the administration did not negotiate in 2013 or later.

Dan Pfeiffer, a senior Obama White House adviser from 2009 to 2015, said Biden is «absolutely» making the right decision in refusing to «allow an extremist minority to use a potential default» to impose bad policy.

“Everybody seems to have forgotten that there was a deadlock on the debt limit in 2013, when Obama took the no-deal approach and prevailed with a clean debt limit,” he said.

Biden’s landscape includes similarities and differences with Obama’s. Boehner had a large majority in the House in 2011 and could afford many defections; today McCarthy can only spend four votes. The Republican Party is more divided now on whether to cut spending on Social Security and Medicare. And Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, who played a pivotal role in the 2011 talks, now turns the onus on McCarthy to find a way forward.

“John Boehner was a weak leader, but he really wanted to avoid default. It is not clear that McCarthy knows what is really at stake or has the intelligence to prevent a breach,» Pfeiffer said in an email.

“On the bright side,” he said, Democrats could try to force a vote on the debt ceiling if just a few Republicans get nervous about the possibility of default. “The narrow majority means that if a clean bill is ever introduced, it only takes a small handful of Republican votes to prevent non-compliance.”